Finding Fuel Solutions For 30,000 Feet

You’re flying comfortably at 30,000 feet, but you may not have noticed a significant problem with your airplane.

Your plane is safe and comfortable, and no oxygen masks have deployed. Your seat is in its upright position, you can turn on your electrical devices, and your bags are stowed carefully under the seat in front of you.

The real problem is your fuel.

Specifically, your cross-country flight is totally dependent on the use of several thousand gallons of petroleum-based jet fuel made from mostly imported oil—a problem if prices rise or if supplies run low.

A LOOK AT THE NUMBERS

In 2011, jet fuel was the biggest expense for airlines—at one third of their total expenses, and jet fuel prices increased by 47 percent in the past year. While fuel costs are a problem for commercial airlines, they are also of concern for the U.S. government, with almost half of its total energy used for jet fuel.

“The airline industry as a whole is very interested in biojet because they want to find an alternative supply to petroleum’s price volatility and to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions.”—Andrew Hawkins

ENTER BIOFUELS

When cars were first invented, they ran on bio-based fuels. Henry Ford used corn-base ethanol to run early Model Ts. Soon, though, petroleum replaced biofuels because it was cheaper and more plentiful.

The airline industry has run solely on petroleum-based fuels, and finding non-petroleum alternatives for jet fuel has become a priority.

In the Pacific Northwest, Sustainable Aviation Fuels Northwest formed in 2010 and brought government and industry leaders, airports, non-profit clean energy organizations, and academics together to try to find sustainable fuel solutions. As in the early days of flight, there have been pioneering efforts to enter a new bio-fuel era. A Boeing flight from Amsterdam to London using palm-based biofuels was the first commercial jet to use biofuels in 2008, and the first bio-fuel, transatlantic flight occurred in 2011.

“The airline industry as a whole is very interested in biojet because they want to find an alternative supply to petroleum’s price volatility and to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions,” said Dr. Andrew C. Hawkins, Team Leader with Gevo Inc., who is coordinating efforts to convert woody biomass to jet fuel for the Northwest Advanced Renewables Alliance (NARA).

HOW DO YOU MAKE JET FUEL FROM WOOD MATERIALS?

NARA researchers aim to provide a biomass-derived replacement for aviation fuel and other petroleum-derived chemicals in a way that is economically and technologically feasible.

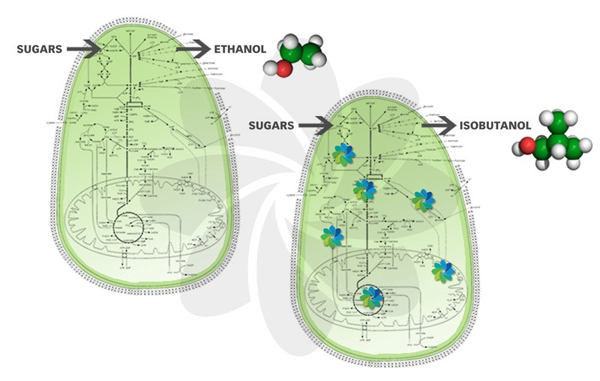

Using pre-treated, woody biomass feedstocks, researchers at Gevo, Inc., a Colorado-based renewable chemicals and advanced biofuels company, aim to use a yeast biocatalyst to produce isobutanol.

Gevo has altered the same type of yeast that you might use to make bread to make isobutanol, an organic compound. The naturally occurring chemical smells vaguely of Juicy Fruit gum and gives strawberries and raspberries their pleasing aroma, says Hawkins.

Gevo has developed a technology to recover the chemical efficiently, taking advantage of the fact that the chemical separates easily from water. The renewable isobutanol can then be converted to jet fuel using chemical processes that are used in the refining industry. Jet fuel made from Gevo’s isobutanol is the same as petrochemical jet fuel except that the carbon source is renewable.

In the past year, the company has successfully converted corn-based feedstocks to isobutanol. They successfully scaled up a demonstration-scale project and are operating a plant in St. Joseph, Missouri, which is able to produce approximately one million gallons per year. They are also retrofitting a 22-million gallon ethanol plant for the production of isobutanol.

The company has signed a non-binding letter of intent to begin supplying aviation biofuel to United Airlines at the Chicago O’Hare International Airport in 2013.

WILL BIO JET FUELS BE SAFE?

That would be the first question when one is flying at 30,000 feet.

Jet fuel made from woody biomass will look, smell, and act exactly like petroleum-based jet fuel, says Hawkins.

“It has to meet all of those properties,” he says.

Gevo is working with ASTM, an international standards organization, to develop a standard for biojet fuel blendstock made from isobutanol. ASTM permits blending of up to 50 percent of an approved biojet fuel with petroleum jet fuel.

To gain approval, a fuel has to pass rigorous testing, and it has to perform exactly like petroleum-based fuel. The three-step process first looks at fuel properties, such as its freezing point and composition. Next, the fuel is tested to see if its chemical and physical properties are compatible with instruments on airplanes. Finally, the fuel is tested in jet engines, and the engines are then disassembled to check on any corrosion or problems. Gevo is in the second part of testing and hopes to have full certification for its biojet fuel by 2013.

CAN BIO JET FUELS BE DONE ECONOMICALLY?

While aviation fuel prices continue to rise, bio jet fuel so far has still been more expensive.

In its business plan, Gevo aims to keep their costs low by retrofitting existing ethanol plants in the U.S., so that they can produce isobutanol. There are hundreds of ethanol plants in the U.S. “This means we don’t have to build a whole new factory—just add on to existing ones,” says Hawkins. “That saves money and means we can produce isobutanol—and ultimately biojet—cheaper.” NARA researchers also aim to develop valuable chemical co-products that can be used as petrochemical substitutes.